Travel health doesn’t exist in isolation. Many health risks encountered by travellers are the same ones that local residents are exposed to every day.

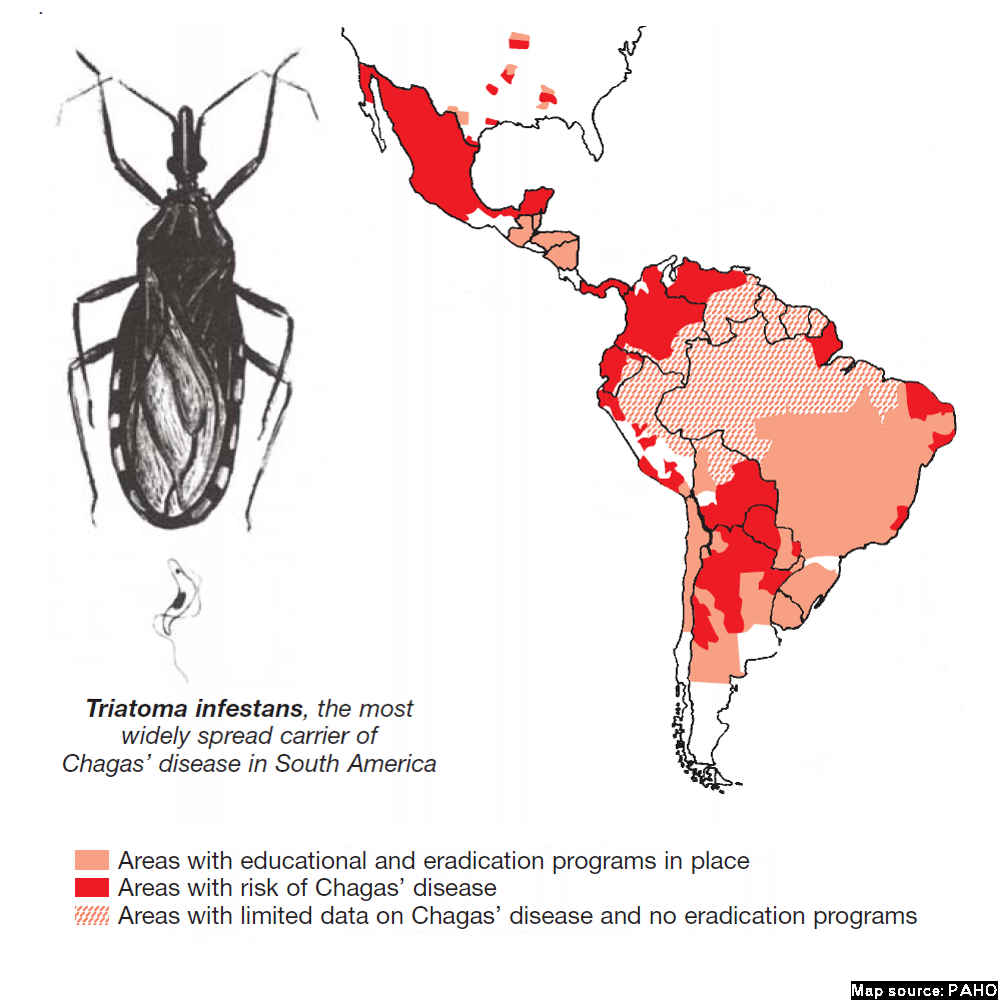

One such risk is Chagas Disease. Although it’s a low risk to most short-term travellers, around 7 million people are infected worldwide – mostly in Central and South America. Due to increasing internal migration (from rural areas to urban areas) and across borders, Chagas has become an international health priority.

In recognition of International Migrants Day, we explore the challenges of controlling Chagas Disease, its impact on global health, and how it disproportionately affects migrating populations.

What is Chagas?

Chagas Disease (also known as American Trypanosomiasis) is named after Dr. Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano Chagas, the Brazilian physician who discovered the disease in 1909. It is caused by the Tripanosoma cruzi protozoa which is transmitted by the triatomine bug – also known as ‘vinchuca’, ‘barbeiro’, or the ‘kissing bug’. The insect is present in Central and South America as well as in the southern United States.

Triatomines often live in wall cracks or thatched roofs. They are active at night and commonly bite the face – which is how they became known as the ‘kissing bug’. Most of the time, bites don’t hurt and a person sleeps through them.

After it bites, the triatomine sheds its feces containing the T. cruzi parasite. It enters the body through the bite wound, a break in the skin, or mucus membrane (mouth or eyes) when a person inadvertently scratches or rubs the site of the bite. Once inside, the parasite travels to the bloodstream and typically targets the heart and the intestines.

Most people who have Chagas do not know they are infected. Initial symptoms, if they occur, are often mild (skin lesion, swollen eye lid, and flu-like symptoms) and appear about 2 months after infection. If left untreated, the disease can cause severe side effects and become life threatening. Approximately 30% of people infected with Chagas can develop cardiac disorders due to untreated infection.

Chagas and migration

In recent years, Chagas has been detected in North America, Europe, and some Western Pacific countries due to migration from Latin America. Transmission of Chagas through the bite of a triatomine bug only occurs in Central and South America and the southern United States. However, people infected with Chagas can transmit the infection to others via blood transfusion or organ transplant. In response, the United States and many countries in Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific now screen for Chagas infection and Canada screens donors for risk of infection. These practices have significantly reduced the risk of acquiring Chagas.

Chagas infection can also be transmitted from an infected mother to her child during pregnancy. In this instance, children of parents who migrated from Latin America can become infected without ever having lived or travelled to an area at risk. In countries where Chagas is endemic, the disease is also transmitted by ingesting food or drinks (acai fruit, guava) contaminated with the T. cruzi parasite.

Controlling the spread of Chagas is challenging due to low awareness among health professionals, even in countries where Chagas is endemic. Chagas is often not detected until later stages – 10-30 years after infection – when irreparable damage has already been done to the heart. One study based in Los Angeles found that Chagas was a frequent reason for pacemaker insertion among Latin American immigrants.

Is Chagas a risk at your destination?

Find out what countries are at risk and how to protect yourself here.

Since its discovery, Chagas has commonly been associated with poverty due to the triatomine bug’s tendency to dwell in poorly constructed houses in rural areas. This has created social stigma towards the disease that often prevents people from getting tested or seeking treatment. This further contributes to the disease going undetected.

As people move to escape poverty or to seek new opportunities, unbeknownst to them, the T. cruzi parasite also travels with them. All travellers – whether we are tourists or migrants – bring health concerns that differ from those at our destination. Together, we all play a role in preventing the spread of disease by ensuring that all people, regardless of where they are during their journey, have access to quality healthcare.

For more information on Chagas disease, check out the following resources:

World Health Organization – Chagas Disease

Doctors Without Borders – Chagas Disease

Photo by Tullia Marcolongo

Article by Daphne Hendsbee & Claire Westmacott