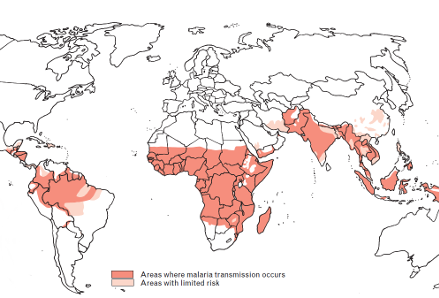

In time for World Malaria Day, we’ve just published our 2015 editions of the World Malaria Risk Chart and How to Protect Yourself Against Malaria.

Not sure if you’re going to a country with malaria? The World Malaria Risk Chart provides detailed descriptions of malaria areas around the world and drug choices for malaria prevention, including information on the maximum altitude that malaria parasites are found, the main mosquito vectors, and the incidence of Plasmodium falciparum, the most deadly form of the 5 malaria parasites to cause illness in humans.

Notable changes this year – Argentina, Costa Rica, Egypt, Greece, Kyrgyzstan, and Sri Lanka no longer report malaria cases.

How to Protect Yourself Against Malaria discusses the behaviour and habits of the female Anopheles mosquito that bites during the night and does not hum, so you don’t hear her. Inside you’ll also find information on all the antimalarials available. If antimalarial medications are recommended for your destination, they are more effective if you also take mechanical precautions such as using a bed net, using repellents with at least 20-30% DEET or 20% Picaridin, and wearing light-weight, light-coloured long-sleeved clothing. All of this information, including antimalarial adult and pediatric dosages, contraindications, and stand-by emergency treatment guidelines are included in this handy guide.

Malaria and climate change

There is evidence that malaria parasites are moving to higher altitudes.

A study published in 2014 compared the number of malaria infections and temperature variation in tropical highlands in Colombia and in Ethiopia from the early 1990s to 2005. Historically, malaria was not endemic in these areas thanks to the cooler climate at high altitudes where the parasites could not mature in the mosquito’s gut: the Anopheles mosquito and the malaria parasites do best in warm, humid climates.

By the end of the study in 2005, temperature increases allowed malaria to reach new heights, infecting more people and at higher altitudes than before. This could create major public health challenges for highland cities that haven’t previously dealt with malaria control. For travellers, this could mean that the areas where malaria protection is recommended may expand to include tropical highlands where malaria wasn’t a concern in the past.